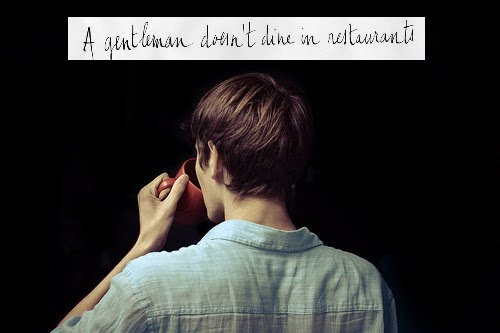

It is rare when I find a portrait

of anyone which suits me, as op-

posed to a blogger's requisites.

This approximate contemporary of

Laurent probably floated up from

the well of Flickr™ into one or

another of those strata where I

search for characterisation of a

phrase in this pursuit. And now

it comes to the page to address

a timely purpose.

Novembr' au revoir.

I heard from a literature student

that he had never read any gay fic-

tion. He is of a generation - the

one we indelicately call, the pres-

ent one - which will never discover

gay fiction as mine did, and by

whose experience whatever is writ-

ten today will be shaped materially.

A number of us, one could almost go

so far as to say, discovered fiction

through gay fiction. That is, we dis-

covered the close reading of imagin-

ative texts through the application,

at an early age, of incentives which

the present generation finds being

met in non-literary terms, all about

it. We didn't know anything, at 11,

19, 27. Surely, there was Classicism.

But that was not about us, we knew.

Harmful as my ignorance was, I still

value the surprises it sequestered.

Somehow, in the same correspondence,

the subject of one's first kiss was

raised. This is why that portrait is

valid to me in ways which nothing I

have read - from Melville to Cunning-

ham - has captured; and this, I know,

is a test that many people apply to

red mug, blue linen. I am grateful.

The single most formative experience

in my college life was not that first

kiss, which did happen there, between

terms. It was another, which happened

the previous Spring. A professor of

history called my bluff on reading the

founding masterpiece of biographical

psychology, in his course in the High

Renaissance, furiously chewing me out

for negligence with - it rings in my

ears to this day - a labour of love.

I was earning grades with him in the

revoltingly prosperous range which is

enough for a Princetonian to acquit

himself without breaking a real sweat.

For my final paper, I raked my way

through his own benchmark work on Ital-

ian rhetoricians; turning, in effect,

straight upon him. His comment was,

"you have a fine sensitivity to texts."

This was my introduction to the kiss,

which is to say, the thing of oneself.

We do some rough and tumble here with-

out much citing of its predicate, and

I owe this youth an answer for his in-

terest. This portrait shows an exer-

cise of consciousness by someone made

intimate to us by the act. We have a

nature which assimilates an articula-

tion of caring as a caring for us.

We know this is the basis of a can-

ard, rooted in unease, that we are

sensitive. It is, rather, that we

are aware we have a bond with that

being, which none of us needs to

hear explained. We know we can watch

the day go down; and we know what is

when we do. Many people do. We are

the ones who are fond of each other

for it.

What is gay fiction?

Herman Melville

Moby-Dick

op. cit.

Michael Cunningham

Flesh and Blood

pp. 130-131 et passim

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1995©

Erik Erikson

Young Man Luther

A Study in Psychoanalysis

and History

Norton, 1958©

Jerrold E. Seigel

Rhetoric and Philosophy

in Renaissance Humanism:

From Petrarch to Valla

Princeton University Press, 1968©